This Edge edition is not dedicated to any one particular hue, but rather to the science behind all human-made color. The global color industry, which centers primarily on pigments and dyes, was valued at 36.4 billion USD in 2021. From 2022 to 2030, it is “expected to expand at an annual compound growth rate of 5.2%” (Grand View Research Market Analysis Report, 2022). However, Andrew Parker, an English inventor, artist, and Zoologist, is bringing attention to an entirely new way of producing color—structural color.

Structural color and pigments each have very different mechanisms of bringing about color. Pigments are molecules that selectively absorb wavelengths of light. When light hits a pigment molecule, it takes in all wavelengths except for the ones that correspond to the shade that the pigment ultimately gives off; those specific wavelengths are scattered into the visible light that the human eye detects as the particular shade. Structural color, on the other hand, is made from intricate nanoscale structures. These formations, often no larger than an atom, reflect light into colored wavelengths rather than absorbing it. The result is extraordinarily vibrant color, often accompanied by a glimmering sheen.

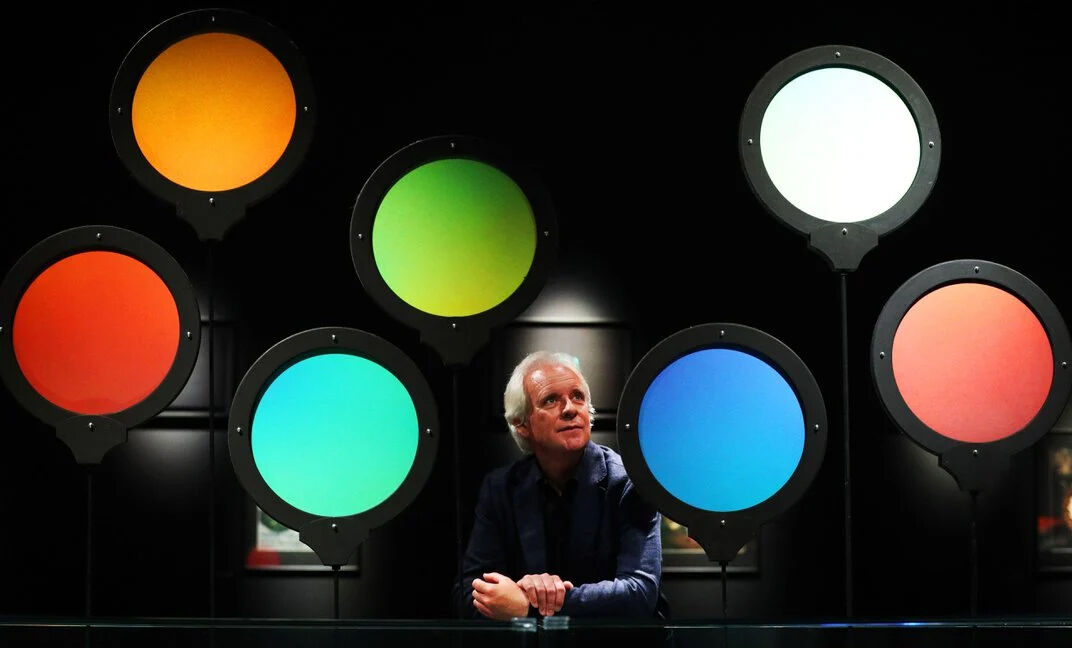

Andrew Parker stands amongst items created from Pure Structural Color at an exhibition at Kew Gardens in 2021.

PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Structural color is often naturally occurring. It was first discovered in peacock feathers in the 17th century, the particular nanostructures found in the dazzling plumage being called “photonic crystals.” The metallic vivacity of many insects is also due to layered nanostructures. Andrew Parker himself had his first encounter with structural color while deep-sea diving; he noticed that, when the sun went down, pigmented animals’ color would fade, while the iridescent hairs of sea lobsters remained vibrant.

For over 20 years now, Parker has been working tirelessly to recreate the nanostructures of structural color in a laboratory. He began by studying vivid beetles under his microscope, finding complex, crystalline architectures. One early attempt involved manually growing the cells of a morpho butterfly, whose wings contain Christmas-tree-shaped nanostructures that give off wavelengths corresponding to a deep blue hue. This method was successful at first, but only briefly, as the cells could not maintain their color.

Over time, Parker perfected a technology that can reliably produce impossibly saturated color. Rich oranges, electric blues, and majestic purples are now industrially manufactured at a factory in the English Midlands. While he is protective over the specifics of his patented invention, Parker has divulged that Pure Structural Color’s exact mechanism can’t be found in nature. “It’s reflecting 100% of the light,” he has said. “’It can’t get any brighter.’”

In 2021, Nike used the product in its prototype of blue and green Air Jordans. Parker has also been working with Swiss chemical company Clariant, developing a technique of mixing flecks of Pure Structural Color into paint. This would allow for the exterior of larger vehicles, like automobiles and airplanes, to be coated in bright, eye-catching shades. A large European airline has already reached out to Parker, interested in replacing pigmented paint on a few sections of their planes.

Structural color represents an innovative new method of producing bright, bold shades. For some inspiration, peruse a few of Ultrafabrics’ most brilliant colors.

744-73323 Montage Chimera

744-14453 Montage Vivid Punch

740-25143 Lino Bosporous

291-4460 Ultraleather Parrot

624-4316 Reef Pro Caribbean